Foundations of Early Medieval Society

A relief image depicting the wife of a Holy Roman

Emperor completing an ordeal to prove her innocence

During the medieval period, society was a mix of classical heritage from ancient Roman and Christian beliefs. However, medieval society was further molded by influences from invading Germanic tribes. One societal custom borrowed from Germanic people was the importance of the family bond, which was extended to husbands, wives, children, siblings, and distant relatives like cousins, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. The German concept of family influenced the treatment of crime and punishment in Germanic law. For example, in the Roman system, murder was considered a crime against the state, whereas in German customs, murder was a personal injury that could be settled in a bloody feud. To avoid bloodshed, however, a system was developed called wergild, or "money for a man," in which a guilty person could pay a monetary amount for his or her offense. In those times, an offense against nobility cost much more than an offense against a peasant or slave.

Another custom of Germanic tribes that European medieval society adopted was the ordeal, which was based on the concept of divine intervention. Specifically, the ordeal involved a sort of physical trial to determine innocence or guilt of an accused person. For instance, after holding a hot iron or retrieving a pebble from the bottom of a boiling cauldron, the wounds of the accused were examined a few days after the ordeal. If the injury was healing well, the accused was proclaimed innocent.

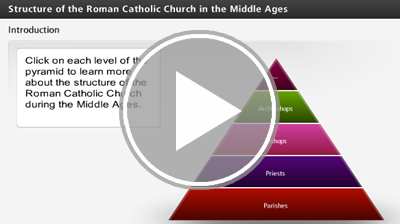

Organization of the Church

Amid the weak central governments in feudal Europe, the Church emerged as a powerful institution. It shaped the lives of people from all levels of society. During the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church developed a hierarchy to organize its people and its practices. In this interactivity, you will learn more about the structure of the Roman Catholic Church. Click the player button to begin.

View a printable version of this interactivity.

Rise of the Pope

Pope Gregory I

Although most Christians accepted the Pope as the supreme leader of the church, they disagreed as to how much power he should have. In the late sixth century, Pope Gregory I, also known as Gregory the Great, significantly strengthened the power of the papacy, or the office of the pope. He heightened his political power by ruling over Rome and the surrounding Papal States, or lands ruled by the pope. As the Church gained political power, it also became increasingly entwined with the feudal system. Church officials came to be selected by feudal lords who chose the clergy based on political alliances rather than spiritual merit. Long before the Roman Catholic Church asserted its authority with German kings in the twelfth century, Pope Gregory I expanded his spiritual authority over Western Europe, and promoted the conversion of Germanic tribes, which he accomplished largely through the monastic movement that you learned about in this topic's warm-up activity.

The Spread of Christianity

Monks helped spread Christianity throughout Europe. Missionaries, or people sent out to carry a religious message, traveled to areas where Germanic tribes lived to spread the Christian faith and the Latin alphabet. Some of the most enthusiastic missionaries were the English and Irish monks.

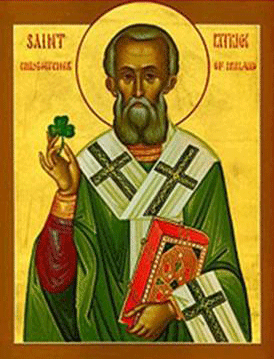

One of the earliest missionaries was Saint Patrick, who at the age of sixteen, was captured by pirates and brought to Ireland as a slave during the fifth century. After six years of captivity, he managed to escape and return home to Roman Britain.

Saint Patrick later decided to serve as a Christian missionary in Ireland, leaving a mark on Irish culture. He is found in many Irish tales, and is said to have taught converted Christians about the Holy Trinity using the three leaves of a shamrock (the four-leaf shamrock, or young sprig of the clover plant, is a rare genetic mutation). Saint Patrick was responsible for converting the sons of kings and wealthy upper class women, some of whom became nuns despite family opposition. While monastic monks were men, women who dedicated their lives to God were called nuns; they lived in convents headed by an abbess. The life of Saint Patrick is celebrated on the anniversary of his death, March 17, known as St. Patrick's Day.

One of the earliest missionaries was Saint Patrick, who at the age of sixteen, was captured by pirates and brought to Ireland as a slave during the fifth century. After six years of captivity, he managed to escape and return home to Roman Britain.

Saint Patrick later decided to serve as a Christian missionary in Ireland, leaving a mark on Irish culture. He is found in many Irish tales, and is said to have taught converted Christians about the Holy Trinity using the three leaves of a shamrock (the four-leaf shamrock, or young sprig of the clover plant, is a rare genetic mutation). Saint Patrick was responsible for converting the sons of kings and wealthy upper class women, some of whom became nuns despite family opposition. While monastic monks were men, women who dedicated their lives to God were called nuns; they lived in convents headed by an abbess. The life of Saint Patrick is celebrated on the anniversary of his death, March 17, known as St. Patrick's Day.